I compiled a list of newspapers (neighborhood, community, school and community, daily, weekly, newsletters, and magazines ) that served or reported on Latinx communities of Chicago. This list includes bilingual, Spanish and English language publications,. Most of these newspapers were published between 1927-1985. I included dates only in cases where I saw only one newspaper, or saw a range of dates. Very few newspapers were archived, and most of what I found were from clippings. NOTE: This is a work in-progress. I began compiling the list in 2016, and will update as I discover more. Please contact me if you would like to share any information. I am working on a guide for locating newspapers and clippings next.

Abrazo (published by MARCH, Movimiento ARtistico CHicano organization)

El Aguila (Benito Juarez HS student paper)

The Anchor (Farragut HS student paper)

El Barzon [Letras y Noticias]

The Chicagoland Community Reporter [Our Community’s Oldest and Best Newspaper] 80s

El Chicago Latino

El Clarin Chicano [Mexican /American] 70s

The Community News (Serving the Near West Side)

Despertador/Get Up Stand Up

¡Exito! [El periódico para toda la familia]

EXTRA [Bilingual Community Newspapers- Spanish/English South Side Editions]

Extra [Sirviendo las comunidades de Pilsen, Lawndale, Little Village]

Get Up Stand Up/Despertador

The Hispanic Times

Chicagoland Community Reporter

El Chicago Latino

El Gallito [Seminario vacilador de chismes, cuentos y caricaturas] 1920s

El Heraldo de Las Americas [Seminario de las Información y Variedades] 20s

El Heraldo [El Periódico Mexicano Para La Colonia Mexicana] 20s

El Heraldo [de Chicago] 80s

Heraldo del Norte

The Hispanic Times [With the truth I neither fear nor offend…] 1980s

El Imparcial de Chicago [Spanish Weekly Newspaper]

El Independiente

El Informador [Eslabón de Cultura Hispano-Americana]

Imparcial de Chicago

Kalpulli News [Vocero de la Comunidad Latinoamericana]

Lawndale News West Side Times [Noticiero Bilingue. Bilingual Newspapers] 80-90s

Latin Times [nadie tiene derecho o lo superfluo mientras alguien carezca de lo indispensable] 68

La Linterna

The Logan Square Free Press

The Lincoln Park Press [People First]

El Mañana [El Primer Diario en Español del Medio Oeste]

El Mañana [weekly]

Mirarte [Chicago’s Latino Art Publication]

Momento

El Norte [the North of Chicago Weekly News]

La Noticia Mundial [El Gran Semanario Hispano-Americano de Chicago] 20s

Nuevo Siglo

Northeast Extra

El Otro

La Opinion [Un Seminario de Todos, Por Todos y Para Todos]

Prensa Libre de Chicago [Midwest’s Largest Spanish-English Newspaper] 70s

Pitirre

La Prensa Adelita [Noticias Comunitarias Latinas. Latino Community News] 90s

Radar Latino [El Crisol Informativo de la Comunidad Hispana] 80s

La Raza El Tiempo[Voz y Expresión de América Latina] 80s

La Raza [Semanario Mexicano Independiente] 20s

Sin Fronteras [Vocero del Trabajador Mexicano]

Sin Fronteras [El Periódico Del Pueblo Obrero Latino. Texas, California, Colorado, Illinois, New York] 70s

Tribuna America

La Verdad [Fraternidad, Accion, Patria] 20s

Venceremos [UFW Chicago newsletter]

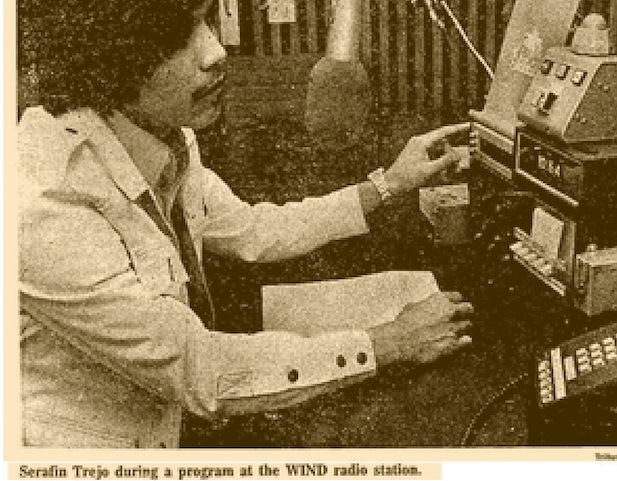

El Viento de Chicago

La Voz de Chicago

Voz del Pueblo [Semanario al Servicio del Trabajadores] 80s

West Side Times [The Paper with Want Ads, pub Sun and Thurs] 80s

Wicker Park/West Town Extra